Teacher mini conferences in class: an alternative to provide feedback in written tasks

Mini conferencias del docente en clase: una alternativa para proporcionar retroalimentación en tareas escritas

Recibido: 15/03/2020

Aceptado: 05/07/2020

Sigüenza Paul1*, Espinoza María-Isabel2

1) Universidad Nacional de Educación, Azogues, Ecuador. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1040-0927 , Email: paul.siguenza@unae.edu.ec

2) Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3574-5729, Email: isabel.espinoza@ucuenca.edu.ec

Para Citar: Siguenza, P. I., & Espinoza, M.-I. (2020). Teacher mini conferences in class: an alternative to provide feedback in written tasks. Revista Publicando, 7(25), 49-63. Retrieved from https://revistapublicando.org/revista/index.php/crv/article/view/2084

Resumen: Hattie y Timperley (2007) definen la retroalimentación como el resultado en el que un agente, como un maestro, proporciona información sobre los aspectos de la comprensión de la persona. La estrategia de retroalimentación que se implementó en este estudio fue mini conferencias de docente en clase. Esta estrategia consiste en actividades previas a la escritura y a la generación de ideas donde el maestro discute con toda la clase e ilustra qué habilidad deben usar los estudiantes (Grabe y Kaplan, 1996). El estudio se realizó en una escuela pública en la ciudad de Cuenca, Ecuador, con estudiantes que aprendían inglés como lengua extranjera (EFL). Consistió en un grupo de intervención (n = 36) y un grupo de control (n = 31). El estudio se realizó durante la primera unidad didáctica (seis semanas) del año escolar 2019-2020 donde los estudiantes produjeron un total de cinco párrafos. El primer párrafo cumplió el propósito de pretest, mientras que el último párrafo fue el post test. La prueba de signos de Wilcox se utilizó para la comparación entre muestras relacionadas (Pre - post) y la prueba de U-Mann Whitney para muestras independientes. Los datos se procesaron a través de SPSS 25. El estudio concluyó que la retroalimentación de los maestros tiene un impacto mayor considerando el desempeño de acuerdo con Yang et al. (2006), Gielen, et al., (2010), Zacharias (2007) y Van den Bergh, Ros y Beijaard (2014). Además, las mini conferencias de docente en clase revelaron un impacto positivo en el desarrollo de ideas de apoyo, organización y transiciones, mecánica y el desarrollo del estilo.

Palabras clave: Mini conferencias del docente en clase, EFL, retroalimentación, Cuenca, Ecuador, escritura, párrafos.

Abstract: Hattie and Timperley (2007) define feedback as the result where an agent, such as a teacher, provides information on the aspects of the person’s understanding. The feedback strategy which was implemented in this study was teacher mini conferences in class. This strategy consists of pre-writing and idea generating activities where the teacher discusses with the whole class and illustrates what skill the students should use (Grabe and Kaplan, 1996). The study was carried out in a public school in the city of Cuenca, Ecuador with students learning English as a foreign language (EFL). It consisted of a target (n=36) and control group (n=31). The study was conducted during the first didactic unit (six weeks) of the scholar year 2019-2020 where the students produced a total of five paragraphs. The first paragraph served the purpose of the pre-test, while the last paragraph was the post-test. The Wilcox sign test was used for comparison between related samples (Pre - post) and the U-Mann Whitney test for independent samples. The data was processed through SPSS 25. The study concluded that teacher feedback has a larger impact considering performance in agreement with Yang et al. (2006), Gielen, et al., (2010), Zacharias (2007), and Van den Bergh, Ros, and Beijaard (2014). Further, teacher mini conferences in class revealed a positive impact on the development of supporting details, organization and transitions, mechanics, and the development of style.

Keywords: Teacher mini conferences in class, EFL, feedback, Cuenca, Ecuador, writing, paragraphs.

INTRODUCTION

In all academic environments, there are key aspects that help learning throughout the teaching process. In the context of teaching English as a foreign language, educators have found several elements that either promote learning or others that obstruct it. As Hyland and Hyland (2006) stated, feedback has long been regarded as essential for the development of second language (L2) writing skills, both for its potential for learning and for student motivation. Although many researchers such as Yang, Badger, and Yu (2006); Gielen, Tops, Dochy, Onghena, and Smeets, (2010); and Gielen, Peeters, Dochy, Onghena, and Struyven (2010) have conducted studies on feedback, the main focus has been allocated to peer-feedback, very little has been researched on mini-class conferences in class to provide feedback in writing assignments. This study aims to analyze the effects of teacher mini-class conferences after students produce written assignments.

As Ion, Barrera-Corominas, and Tomàs-Folch (2016) have pointed out, feedback has a clear purpose, to develop autonomous learners that can think reflectively and adopt self-directed attitudes regarding their lifelong learning. These authors concluded that in an EFL learning context, several teachers had a specific and stablished method to give feedback and did not look for alternatives that could possibly help students, acknowledging the diversity of their learning process in their classrooms.

However, Paulus (1999) determined that revision does not always mean improving the quality of a written task. This could be caused due to the lack of clearness, purpose, meaning, and compatibility that teachers' feedback has with students' prior knowledge resulting in deficiency in logical connections (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Van den Bergh, Ros, and Beijaard (2014) claimed that most research done on feedback has been examined in traditional learning contexts where the priority has been to change or confirm students' knowledge. Nicol and Macfarlane‐Dick (2006) claimed that there is not a clear agreement on defining quality feedback in active learning.

On the other hand, Zacharias (2007) established that a variety of attempts have been performed to help students improve their writing quality through feedback; in the words of this author, despite the efforts by English teachers, students do not improve their writing tasks and keep making the same mistakes. In this manner, several concerns arise. As Hyland and Hyland (2006) stated, an issue that is permanently presented in feedback is its degree of quality. Gamlem and Smith (2013) suggested that feedback processes need to be modified to help students improve in future tasks. As a result, this study focuses on analyzing a specific feedback process and the possible effects of the application of it. In agreement with Zacharias (2007), students keep making the same errors and mistakes in their tasks after the feedback is conducted.

Feedback definitions and relevance in teaching

Hattie and Timperley (2007) wrote that feedback is the consequence of performance where an agent, such as a teacher, book, experience, among others, gives information on the aspects of the person 's understanding. Voerman, Meijer, Korthagen, and Simons (2012) concluded that feedback can be interpreted as the previous level of performance of a student, an outside intervention with a desired objective or goal, and the new current level of performance of the same student.

Feedback helps students maximize their potential in different stages of their training and learning process by identifying strengths and areas of improvement. This aspect allows the development of new action plans to improve skills (Alirio & Zambrano, 2011). Van den Bergh, Ros, and Beijaard (2014) determined that feedback must be centered on developing metacognition in students, as well as knowledge of their socio-cultural skills as the teacher coaches them throughout the teaching-learning process.

Teachers' feedback is still considered the most effective method. This perspective does not only come from students' statements, but also from the teachers. Even when students are asked to provide feedback, most of the time, they will go to the teachers and ask if the comments they are making to their classmates are accurate (Zacharias, 2007).

Teachers and students find frustration regarding the feedback process and may find it even disappointing. Therefore, providing timely feedback has become crucial to develop competencies and constantly motivate the students Mahsood, et al. (2018). According to these authors, it is necessary to administer formative feedback to positively impact the students' learning stating that the quality of information provided by the teacher will influence on the students' performance.

Teacher mini conferences in class

This technique is part of the teacher-student responses. It involves several ways that this technique can be applied. For instance, talking about pre-writing and idea generating activities where the teacher discusses with the whole class and illustrates what skill the students should use; also, teachers should have students write evaluations of their written drafts and discuss those evaluations; further, the teacher can use a specific writing or writings from the students to lead to discussions of problems that students share; moreover, a teacher can work with a volunteer to analyze the writing and receive feedback from the entire class; finally, the teacher can apply language learning activities such as scrambling sentences, highlight opinions and arguments and discuss their effectiveness (Grabe and Kaplan, 1996).

Studies on feedback interventions

Zacharias (2007) confirmed in his study on teachers' and students' attitudes towards teacher feedback that teacher feedback is an important tool to improve students writing, according to the following reasons in favor of teacher feedback: teachers have higher linguistic competence in English, teacher feedback provides security for the students, cultural belief that teachers are the source of knowledge, and teachers control grades. Similarly, Yang et al. (2006). compared peer and teacher feedback by means of analyzing students' written drafts. The results demonstrated that students received 65.6% more feedback per word from their teacher compared to their peers' feedback. Also, students incorporated 90% of the feedback when it was provided by the teacher against 67% from their peers. Finally, interviews were applied to the students where they stated that teachers' feedback was more professional, experienced, and trustworthy than their peers. These authors demonstrated that teacher feedback leads to greater improvement due to the perception that teacher feedback is more qualified, experienced, accurate, valid, reliable and trustworthy. However, Zacharias (2007), claimed that not all students agree, especially the ones who have received inappropriate teacher feedback such as: too much feedback or the use of unknown terms.

Further, a study on teacher and peer feedback in writing was performed in a secondary school by Gielen, et al., (2010) where similar results to Yang et al. (2006) were recorded. Based on students' perceptions, 56% of students did not consider peer feedback to be useful, and 63% of the students did not wish to continue using peer feedback. Both studies by Gielen et al. (2010) and Yang et al. (2006), agreed that teacher feedback has a larger impact considering performance. Moreover, Rajab, Khan and Elyas (2015) aimed to identify teachers' perceptions in EFL (n =184) and practices in Written Corrective Feedback (WCF) in the Saudi context found “time” as the main factor in following a particular strategy for written corrective feedback.

Voerman, Meijer, Korthagen, and Simons (2012) found that feedback interactions are low, and most are non-specific. However, specific feedback is among the most relevant tools to influence students' learning (Hattie, 1999). Moreover, Van den Bergh, Ros, and Beijaard (2014) conducted a study in Netherlands where 47 primary schools were considered. The research pointed out that around 50% of teacher-student interactions are regarded to feedback, precisely on assignments that students are working or on process. The authors affirm that very few of these interactions have non-specific feedback or feedback focused on personalities.

Baker and Hansen Bricker (2010) conducted a research on native English and ESL speakers' perception on writing feedback. They found that both speakers were able to quickly identify positive and negative comments when they were direct. However, both speakers were slow to identify positive and negative comments when they were indirect suggesting that students easily understand feedback when they are praised, but when comments are negative, students take longer to understand them. It helps explain why some students do not make changes in their works after the teacher has illustrated some errors. In addition, Burnett (2002) concluded that students, who perceived that the teacher was constantly giving them negative feedback, reported a negative relationship with the teacher while impacting on the classroom environment in a negative way. Thus, the author suggested that students' satisfaction is determined by the positive feedback that the teacher provides.

Kazemi, Abadikhah, Dehqan (2018) conducted a study to compare teacher-written feedback with joint feedback of student reviewers after intra-feedback session. A group of twenty-one university students and an EFL teacher participated in the study. From the results, it was found that both teacher and students were concerned with surface-level errors during peer feedback and indicated less engagement with other aspects of the composition such as content and organization.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

This study was a quantitative research. The study was framed under this approach to analyze the effects of teacher mini class conferences on writing paragraphs, from a statistical view and from students' perceptions. Thus, it will be developed by integrating numerical results and students' points of views of this type of feedback. In agreement with Millsap and Maydeu-Olivares (2009), this study was quasi-experimental because it tested the effects of a particular type of teacher feedback in a unit (classroom) and did not focus on applying different treatments (feedback methods) to individuals. The study has an independent variable: teacher mini conferences in class and the dependent variable: paragraph structuring.

This research was done similarly to Byram, Gribkova, and Starkey (2002) with a pre-test, treatment, post-test, quasi-experimental design in which the collected data will be analyzed quantitatively. For the perception analysis, a survey was conducted.

The study was conducted with 67 students made up of groups; the first, the “target group” with 36 participants: 30 men and 6 women between 14 and 16 years old. The other, the “control group” with 31 students: 28 men and 3 women between 14 and 16 years who regularly attended the English class during the period September - October 2019 a public primary school, a public institution of the city of Cuenca.

The application of the teacher mini-class conferences was conducted during the first didactic unit (six weeks) of the scholar year 2019-2020. During this time, the students produced a total of five paragraphs. The first paragraph served the purpose of the pre-test, while the last paragraph was the post-test. In the target group, after the students had finished writing each paragraph, the teacher provided feedback through mini-class conferences. Meanwhile, in the control group, the teacher was free to provide feedback as she wished. After the feedback was given, the students were asked to write the next paragraph.

Data collection and analysis

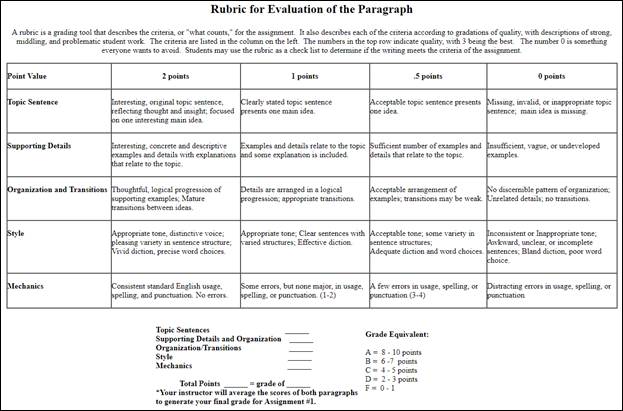

The instruments that were used in this study for the analysis were: the five written assignments, to collect the data; and the survey to analyze the students' perceptions. To grade the students' paragraphs, Brown's basic paragraph rubric was used from Mesa Community College (Appendix 1) on a scale from zero to two for each criterion.

The analysis is presented using measures of central tendency and dispersion, the behavior of the data was not normal according to the Kolmogorov Smirnov test (p <0.05). Consequently, non-parametric tests were used; the Wilcox sign test for comparison between related samples (Pre - post) and the U-Mann Whitney test for independent samples. The decisions were made with a significance of 5% (p <0.05). The data processing was done in the statistical program SPSS 25, and the editing of tables and graphs in Excel 2019.

RESULTS

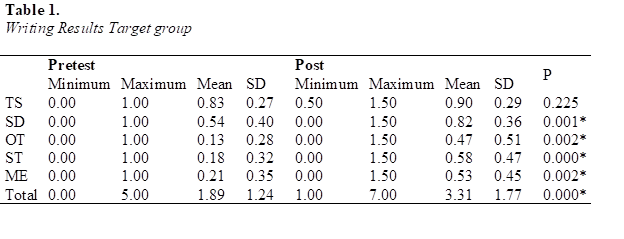

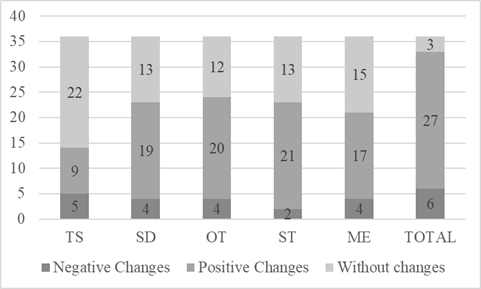

The results of the pre-test showed that each of the sub-skills before the intervention reached a maximum of 1 with a mean lower than 1, indicating a “moderately appropriate” level in each of them; topic sentence was the sub-skill with the best performance within this group (M = 0.83; SD = 0.27), followed by supporting details (M = 0.54; SD = 0.40), while the weakest performance sub-skill was organization and transition. After the intervention, a similar behavior was found in the development of sub-skills. However, a significant improvement was found in the total writing performance, and in 4 of the 5 sub-skills evaluated except in topic sentence.

Note: *Significative difference (p<.05). TS=Topic Sentence, SD= Supporting Details, OT= Organization and transitions, ST= Style, ME= Mechanics

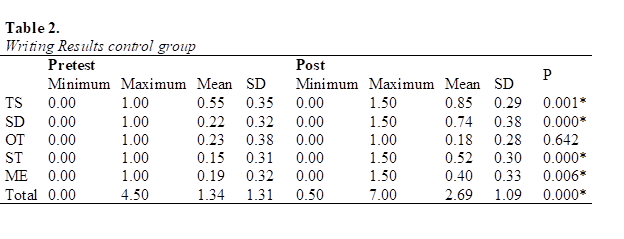

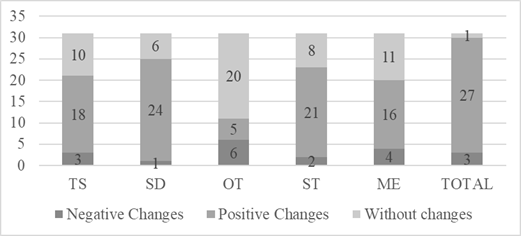

In the control group, before the intervention, a general oscillating performance was found between 0 and 1 with average scores close to 0.5 which implies a poor level of writing. It was found that the best developed sub-skill was topic sentence (M = 0.55; SD = 0.35) followed by supporting details (M = 0.22; SD = 0.32), with style being the weakest sub-skill within this group. The results of the post-test had maximum scores of 1.5 and average scores close to one in each of the sub-skills following a similar pattern of performance except organization and transition, that proved to be the weakest in the post-test, being also the only one not to reflect a significant difference between before and after.

Note: TS=Topic Sentence, SD= Supporting Details, OT= Organization and transitions, ST= Style, ME= Mechanics.

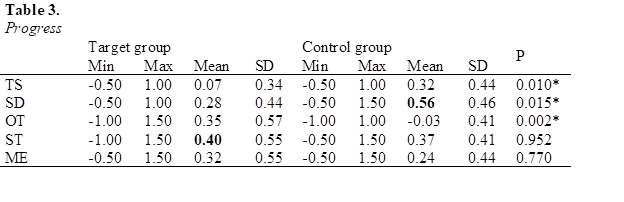

The changes registered in the students from both groups had a maximum decrease of one point and a maximum increase of 1.50. It was also found that the style sub-skill was the one with the greatest progress (M = 0.40; SD = 0.55), while in the control group it was supporting details (M = 0.56; SD = 0.46). Differences were also found significantly in topic sentence and supporting details (p <.05), the students from the control group had significantly greater progress. In the contrary, in organization and transitions, the target group presented progress, and the control group setbacks (p <. 05).

Note: TS=Topic Sentence, SD= Supporting Details, OT= Organization and transitions, ST= Style, ME= Mechanics.

As demonstrated in table 4, at least 9 students showed positive changes (progress) in some of the sub-skills. 13 students showed this in supporting details, organization and transitions, style, and mechanics. On the other hand, regarding the sub-skill of topic sentence, there were no changes in 22 students representing the sub-skill with fewer changes. Finally, considering the final grade, overall, 27 students progressed in their writing.

Table 4.

Target group changes.

Note: TS=Topic Sentence, SD= Supporting Details, OT= Organization and transitions, ST= Style, ME= Mechanics.

The results from the control group revealed that at least 16 students had registered positive changes in the sub-skills: topic sentence, supporting details, style, and mechanics. While in organization and transitions, there were 20 students who did not recorded changes.

Table 5.

Control group changes

Note: TS=Topic Sentence, SD= Supporting Details, OT= Organization and transitions, ST= Style, ME= Mechanics.

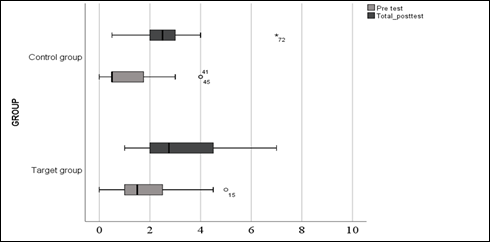

Finally, table 6 shows that the overall performance of the students, on average, was less than 4 points, indicating that the students did not reach the required learning as stipulated by the Ministry of Education. However, there was an average change of 1.42 points (SD = 1.87) in the treatment group and 1.47 (SD = 1.45) in the control group. The target group revealed, in the post test, a high dispersion, which implies a heterogeneous behavior in the students, while the control group presented a quite homogeneous behavior.

Table 6.

Pretest and Posttest.

Note: TS=Topic Sentence, SD= Supporting Details, OT= Organization and transitions, ST= Style, ME= Mechanics.

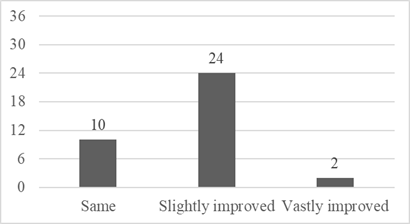

Perceptions

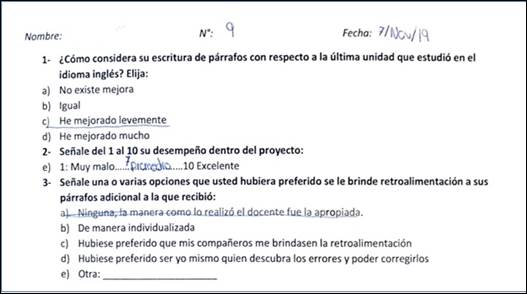

The results revealed that the writing of paragraphs with respect to the last unit studied in the English subject (prior to the intervention), had improved slightly (n = 24), in most of the students. In addition, 10 students considered a same performance, and 2 mentioned a high improvement.

Table 7.

Perception about improvement on their Writing

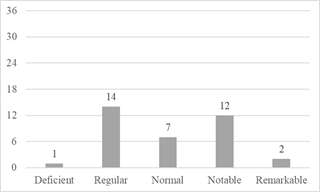

The students' self-assessment, considering their performance within the unit, revealed an average score of 3 (SD = 1.04); generally reflecting a satisfactory level. It was also found that 14 students considered their performance regular, and 12 notable.

Table 8.

Self-appraisal

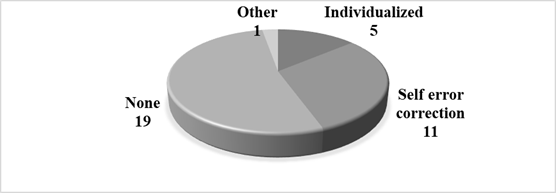

The suggestions from the students regarding the feedback revealed that more than half (n=19) considered that the way the teacher applied it, was adequate. Further, 11 people preferred to be themselves, who discovered their mistakes. And, a minority (n=1) would have preferred a personalized feedback.

Table 9.

Students’ suggestions

DISCUSSION

The results established in the post-test, after the teacher mini class conferences were applied in the target group, demonstrate that the unique subskill students did not show a significant difference was topic sentence (p = 0.225). However, in the control group, organization and transitions was the subskill that did not evidence a significant improvement (p=0.642). These results seem to be in line with Kazemi, Abadikhah, Dehqan (2018) where students are mainly concerned with surface-level errors during feedback and pay less attention to aspects of composition such as organization. On the other hand, after the intervention, in the target group, style was the sub-skill with the greatest progress (M = 0.40; SD = 0.55); while in the control group, it was supporting details (M = 0.56; SD = 0.46).

Overall, the target group presented improvement in their writing in a total of 27 students. In the control group, 16 students showed a general progress. Since both groups received feedback mainly from their teachers, it resembles Zacharias (2007) who determined that teacher feedback is an important tool to improve students' writing due to higher linguistic competence in English and provides security for the students. Consequently, both groups show a significant difference in 4 out of the 5 subskills.

Voerman, Meijer, Korthagen, and Simons (2012), concluded that feedback interactions between the teacher and the students, are low, and most are non-specific. Notwithstanding, after the intervention and as evidenced in the post test, there was an average change of 1.42 points (SD = 1.87) in the target group and 1.47 (SD = 1.45) in the control group. Surprisingly, the target group, which received mainly a high level of interactions, revealed a heterogeneous behavior in the students based on a higher dispersion in their positive changes, while the control group, which received a low level of interactions, presented a more homogeneous behavior.

Regarding students' perceptions in the target group (n = 36), most of them (24) claimed that their paragraph writing had improved slightly, and only 2 mentioned a high improvement. These results agree with their average in the pre-test (1.89) when compared to the post-test (3.31). Their average reveals a significant improvement, but not a high significance to be considered. Since much of the feedback was positive, it will agree with the suggestions from Baker and Hansen Bricker (2010), that students easily understand feedback when they are praised. However, the study showed how involved they were in the writing from their own points of view after the teacher mini class conferences revealing somewhat of a lack of commitment. More than half of the class (22) felt their own participation to be normal to deficient.

Students mainly have positive attitudes towards the type of feedback given. The results yielded similarities to the studies conducted by Yang et al. (2006), Gielen, et al. (2010), Zacharias (2007), and Van den Bergh, Ros, and Beijaard (2014), all of whom established that teacher feedback has a larger impact considering performance. This statement is supported by the fact that most students (19) did not want to make any changes to the way the feedback was provided to them.

CONCLUSIONS

Teacher mini conferences in class as a mean of feedback revealed a positive impact on the development of supporting details, organization and transitions, and mechanics. Moreover, the larger impact, that this type of feedback seems to have, is on the development of style rather than other subskills. On the other hand, teacher mini class conferences do not show a significant improvement in the development of topic sentences.

Students benefited by conducting this type of feedback, as evidenced in the target group where 26 learners improved their overall paragraph writing. However, traditional teacher feedback also provided a fair amount of improvements on students’ (16) writing process. Also, the study concludes that significant differences are shown in topic sentence and supporting details (p <.05) since students from the control group had significantly greater progress in these two subskills, than the ones from the target group.

Most of the students found teacher mini conferences in class to be appealing to them. Therefore, it is relevant to implement this type of feedback after writing assignments. Furthermore, students agree that teacher feedback is more meaningful and can bring greater improvement to their writing tasks. Nevertheless, it is important to take into consideration that this technique could cause a heterogenous behavior in the results of the students´ writings. Consequently, further research is needed to understand the reasons for these results.

The results may vary depending on different variables and other contexts. New research, related to this topic, could focus on comparing this type of feedback to peer-feedback, in this context, considering that some students did want their classmates to provide it. Also, this feedback strategy could be applied to different levels of proficiency and ages. Finally, it could be studied possible outcomes that include not only public education, but private education as well.

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

Alirio, E., & Zambramo, L. (2011). Characterizing the feedback processes in the teaching practicum. Entornos. 24(1), 73-85.

Baker, W., & Hansen Bricker, R. (2010). The effects of direct and indirect speech acts on native English and ESL speakers’ perception of teacher written feedback. System, 38(1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2009.12.007

Burnett, P. C. (2002). Teacher praise and feedback and students' perceptions of the classroom environment. Educational Psychology, 22(1), 5–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410120101215

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers. Council of Europe. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.ec/books?id=f00SnQEACAAJ

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2003). Research methods in education. London; New York: RoutledgeFalmer. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=77071

Gamlem, S. M., & Smith, K. (2013). Student perceptions of classroom feedback. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 20(2), 150–169. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2012.749212

Gielen, S., Peeters, E., Dochy, F., Onghena, P., & Struyven, K. (2010). Improving the effectiveness of peer feedback for learning. Learning and Instruction, 20(4), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.007

Gielen, S., Tops, L., Dochy, F., Onghena, P., & Smeets, S. (2010). A comparative study of peer and teacher feedback and of various peer feedback forms in a secondary school writing curriculum. British Educational Research Journal, 36(1), 143–162. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902894070.

Grabe, W., & Kaplan, R. B. (1996). Theory and practice of writing. London: Longman.

Hattie, J. (1999). Influences on student learning. Inaugural lecture, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487.

Hyland, K., & Hyland, F. (2006). Feedback on second language students’ writing. Language Teaching, 39(02), 83. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444806003399

Ion, G., Barrera-Corominas, A., & Tomàs-Folch, M. (2016). Written peer-feedback to enhance students’ current and future learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-016-0017-y

Kazemi, M., Abadikhah, S., & Dehqan, M. (2018). A comparison of teacher feedback versus students’ joint feedback on EFL students’ composition. The IUP Journal of English Studies, 13(1), 90–102.

Mahsood, N., Jamil, B., Mehboob, U., Kibria, Z., & Khalil, K. U. R. (2018). Feedback. The Professional Medical Journal, 25(01), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.29309/TPMJ/18.4242

Millsap, R. E., Maydeu-Olivares, A., Sage Publications, & Sage eReference (Online service). (2009). The Sage handbook of quantitative methods in psychology. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage. Retrieved from http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=743581

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane‐Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

Paulus, T. (1999). The effect of peer and teacher feedback on student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 8(3), 265-289.

Rajab, H., Khan, K., & Elyas, T. (2016). A case study of EFL teachers’ perceptions and practices in written corrective feedback. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 5(1), 119-128.

Van den Bergh, L., Ros, A., & Beijaard, D. (2013). Teacher feedback during active learning: Current practices in primary schools: Teacher feedback during active learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(2), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02073.x

Van den Bergh, L., Ros, A., & Beijaard, D. (2014). Improving teacher feedback during active learning: Effects of a professional development program. American Educational Research Journal, 51(4), 772–809. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214531322

Voerman, L., Meijer, P. C., Korthagen, F. A. J., & Simons, R. J. (2012). Types and frequencies of feedback interventions in classroom interaction in secondary education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(8), 1107–1115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.06.006

Yang, M., Badger, R., & Yu, Z. (2006). A comparative study of peer and teacher feedback in a Chinese EFL writing class. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15(3), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2006.09.004

Zacharias, N. T. (2007). Teacher and student attitudes toward teacher feedback. RELC Journal, 38(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688206076157

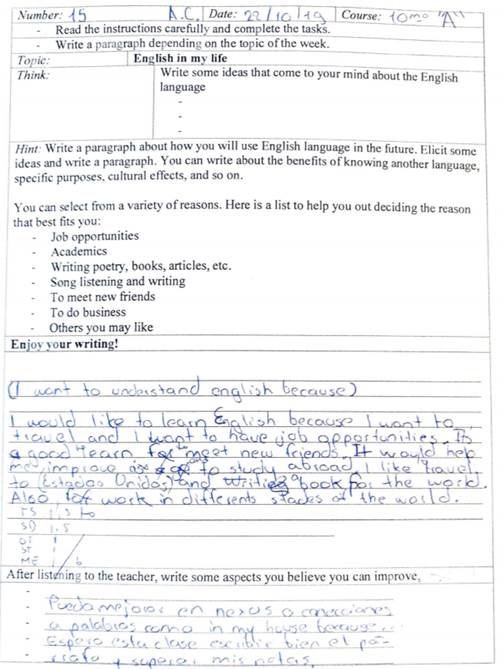

APPENDICES

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Writing assignments

Appendix 3

Survey