An overview of undergraduate students’ perceptions on content-based lessons taught in English: An exploratory study conducted in an Ecuadorian university

Panorama de las percepciones de estudiantes de grado sobre clases basadas en contenido impartidas en inglés: Un estudio exploratorio llevado a cabo en una universidad ecuatoriana

Diego Ortega-Auquilla1, Paul Sigüenza-Garzón2, Sara Cherres-Fajardo3, Andrés Bonilla-Marchán4

Universidad Nacional de Educación, Azogues, Ecuador

1* Email: diego.ortega@unae.edu.ec ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6256-9150

2. Email: paul.siguenza@unae.edu.ec ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1040-0927

3. Email: sara.cherres@unae.edu.ec ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5150-8881

4. Email: andres.bonilla@unae.edu.ec ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5929-8265

Recibido: 23/01/2021

Aceptado: 23/03/2021

Como Citar: Ortega-Auquilla, D., Sigüenza-Garzón, P., Cherres-Fajardo, S., & Bonilla-Marchán, A. (2021). Panorama de las percepciones de estudiantes de grado sobre clases basadas en contenido impartidas en inglés: Un estudio exploratorio llevado a cabo en una universidad ecuatoriana. Revista Publicando, 8(29), 65-78. https://doi.org/10.51528/rp.vol8.id2183

ABSTRACT

Currently, the English language has both an important role in university studies and professional careers. With that in mind, the present study employed an exploratory research approach to determine university students’ perceptions with regard to learning course content on curriculum and education-related topics through the implementation of content-based lessons taught in the English language. A survey was administered to 171 students in different majors from one public university in Ecuador. The close-ended questions focused on learning about the respondents’ perceptions concerning varied statements, such as the importance and suitability of the use of English for the learning-teaching process of university subjects, the helpfulness and impact of learning content through the implementation of class sessions taught in English. Furthermore, an open-ended question was put forward to find out in what ways the learning of university subjects taught in English may help the study participants in the future. The findings showed that a large number of respondents had positive attitudes towards learning content-based lessons about the education-related subject matter in English, as they found this instructional process helpful in terms of class participation, motivation, critical thinking, and other aspects. It was concluded that students could better learn the English language in a more genuine manner by means of lessons directed by CLIL, as they complete essential undergraduate courses from their field of study at the university level.

Keywords: University Students, English Language, Learning, Content-Based Lessons,

CLIL.

RESUMEN

Actualmente, el idioma inglés cumple un papel importante tanto en los estudios universitarios como en las carreras profesionales. Teniendo esto en cuenta, el presente estudio empleó un enfoque de investigación exploratorio para determinar las percepciones de estudiantes universitarios con respecto al aprendizaje de contenidos centrados en temas de currículo y educación a través de la implementación de lecciones impartidas en idioma inglés. Se administró una encuesta a 171 estudiantes de diferentes carreras de una universidad pública en Ecuador. Las preguntas cerradas se enfocaron en conocer las percepciones de los encuestados con respecto a varias afirmaciones, tales como la importancia e idoneidad del uso del inglés para el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje de asignaturas universitarias, la utilidad y el impacto del aprendizaje de contenidos a través de la implementación de sesiones de clase en inglés. Además, se planteó una pregunta abierta para averiguar de qué manera el aprendizaje de las materias universitarias impartidas en inglés puede ayudar a los participantes del estudio en el futuro. Los hallazgos mostraron que una gran cantidad de encuestados tenían actitudes positivas hacia el aprendizaje de lecciones basadas en contenido sobre materias relacionadas con la educación en inglés, ya que encontraron este proceso de instrucción útil en términos de participación en clase, motivación, pensamiento crítico y otros aspectos. Se concluyó que los estudiantes pueden aprender mejor el idioma inglés de manera más genuina a través de lecciones dirigidas por CLIL, ya que completan cursos de pregrado esenciales de su campo de estudio a nivel universitario.

Palabras clave: Estudiantes Universitarios, Idioma Inglés, Aprendizaje, Lecciones Basadas en Contenido, CLIL.

INTRODUCTION

Many people around the world have been encouraged to learn the English language due to the globalized political, economic and educational needs. English is a second language (L2) of utmost importance in the academic and professional life of university students and has been considered by them as a potential source for a better life development. However, it is important to consider that the acquisition of a L2 goes beyond the teaching and learning of grammatical structures and isolated words. Throughout the years, several pedagogical models and approaches have enriched the educational field, therefore, this study is focused on the application of Content Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), specially, in university classrooms.

Since the mid-1990s, CLIL is a form of education mainly applied in Europe that is also extending through continents as an educational approach (Coyle, Hood, and Marsh, 2010) and its usage keeps growing rapidly (Pérez-Cañado, 2012). Currently, the term has gained reputation among teachers and researchers involved in teaching English as a foreign language (EFL), mainly (Georgiou, 2012), consequently, it is becoming a paramount focus of study.

In Ecuador, the national curriculum (2016) intends to englobe the needs of the Ecuadorian educational reality and also pretends to guarantee appropriate conditions to learn the L2. Through a ministerial agreement in (2016), English language teaching was stablished as mandatory within the curriculum. However, the implementation of CLIL in Ecuadorian universities is still under expansion. This research is being conducted at the Universidad Nacional de Education UNAE, in which students, who are currently studying CLIL as part of their undergraduate major, were surveyed to identify the empathy that they have towards the subject and its future relevance in their academic, professional or personal life.

CLIL has been defined as “a dual-focused educational approach in which an additional language is used for the learning and teaching of both content and language” (Coyle, Hood, and Marsh, 2010). Thus, the teaching of content through a L2 has deliberately created a challenge for language learning. The purpose of raising the standards of proficiency in a L2 acquisition, respecting the national curriculum and giving the correspondent importance to the teaching of content, has promoted this research to examine the advantages and disadvantages of CLIL in a university atmosphere.

Research has demonstrated that the fusion between content and language is feasible and well accepted by pupils (Admiraal et al., 2006; Verspoor et at., 2015). In addition, CLIL teachers are conscious that the language development is a big part of their responsibility (de Graaff et al., 2007), and consequently, as mentioned by Coyle (2007) teachers are aware that through language, students are able to learn a specific subject, as well as content that enables pupils to acquire language.

Koopman et al. (2014), state as an interesting fact, that the majority of CLIL teachers are L2 speakers which means that their awareness about the challenges of acquiring a L2 is evident. Also, it is worth mentioning that “at any language level and at any cognitive level, pupils who learn content also need to develop their language” (Llinares et al., 2012). Georgiou (2012) mentions that teachers and experts see CLIL as a source to improve language education; therefore, every teacher who is teaching a content subject, should consequently be a language teacher.

In this perspective, considering the students’ responses in the applied surveys, CLIL can be seen as a main factor to enhance their future life conditions and expand their language potential.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Content-Based Instruction

Content-based approach is a pedagogical framework which facilitates form-meaning connections in the field of second language acquisition (Mart, 2019). Content-based instruction (CBI), as an approach to teach a second language, does not focus on the language itself; but rather on the information input that the students will acquire (Richards & Rodgers 2014). Waller (2018) defines CBI, from a language learning perspective, as teaching linguistic elements through materials that are discipline-specific to an academic field (i.e., business, history, etc.). The purpose of CBI is to teach content by using a foreign language (Kang, 2007). Consequently, as Sato, Hasegawa, Kumagai, and Kamiyoshi (2017) state, CBI has been widely accepted and adopted in language programs across the world.

CBI could make different linkages on these three levels: connections between language education and other academic fields, language education and education at large, and language education and society (Sato, Hasegawa, Kumagai & Kamiyoshi, 2017). In the Higher-Education context, Lou and Xu (2016) found out that CBI English teaching could improve the level of English language applied ability of non-English-majored undergraduate students in their English learning. Vergara, Lopez, Macea, and de la Rosa (2016) determined, by a study conducted in Higher-Education in Colombia, that CBI improved the students' proficiency in the language and the academic knowledge. Further, second language (L2) learners thought that, by using CBI, the class was challenging since they had to pay attention not only to the language but also to the content that was the focus of the course (Vergara et al., 2016).

Mcdougald (2017) determined areas that would provide all practitioners with a starting point to reflect on when considering how to approach language and content in the classroom. First, content area: educators must be well-versed in the content subject area that they teach. Next, pedagogy: educators must be prepared to implement strategies that provide students with opportunities to access content in pedagogically valuable ways and employ a range of evaluation options to evaluate both content learning and language learning. Then, Second Language Acquisition (SLA): educators need to understand how learner language acquisition develops and evolves over time to facilitate the process. Afterwards, Language Teaching: teachers need to know how to support the use and development of the “four skills” (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) of language in their classes. Finally, materials selection and adaptation: educators must be able to select and, as necessary, adapt a variety of methods, approaches, instructional materials to meet the language/linguistic needs of their students.

From Content-Based Instruction to Content Language Integrated Learning

Cenoz (2015) analyzed the differences and similarities between CBI and Content Integrated Learning (CLIL) concluding that both share the same essential properties and are not pedagogically different from each other; moreover, a second language (L2) as the medium of instruction, the language, societal and educational objectives and the learners are the same in CBI and CLIL. Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010) defined CLIL as a dual-focused educational approach in which an additional language is used for the learning and teaching of both content and language. Similarly, Stoller (2008) considered that CBI is ‘an umbrella term’ for approaches that combine language and content learning objectives even if there are differences in the emphasis placed on language and content.

Content Language Integrated Learning in Higher Education

In the case of CLIL, Pladevall-Ballester (2018) suggested that it boosts learners’ motivation to learn a foreign language even in low exposure situations. Spanish higher education and post-graduate students have a positive view of CLIL after integrating the learning of English as a foreign language into the curriculum of other content areas through the reorganization of subject syllabi (Martin de Lama, 2015). Also, Guadamillas (2017) analyzed future teachers’ perceptions of this approach and concluded that most of them consider CLIL useful and that they positively valued the opportunities to apply the classroom methodology in semi-real situations.

In the Ecuadorian Higher Education context, Argudo, Abad, Fajardo-Dack, and Cabrera (2018) stated that the parameters teachers used to plan their classes did not consider the three dimensions of this approach (content, language, and procedures); therefore, students are not developing these dimensions simultaneously.

Although debates on how to best achieve the effective integration of content and language teaching have been going on for decades, it must be admitted that few firm conclusions and little consensus have been reached (Mcdougald, 2017). Tsuchiya and Perez (2015) stated that CLIL is still controversial, as evidenced by students from Japan and Spain, who critically addressed various concerns and difficulties in implementation of CLIL at universities i.e. their insufficient English skills to understand subjects and the potential risk to lack subject knowledge in their first language (L1). This is in line with Yang´s (2016) findings that mainly revealed that learners’ satisfaction with the CLIL approach is greatly affected by their level of language proficiency.

METHODOLOGY

The present study, which took place in one public university in the southern part of Ecuador in the highland’s region, adopted an exploratory research approach. As stated by Reiter (2017), new explanations are to be found out through exploratory research, especially explanations that have been previously overlooked. This can be done through a “process of amplifying [researchers’] conceptual tools to allow [them] to raise new questions and provide new explanations of a given reality from a new angle” (p. 144).

As indicated before, the aim of the research study was to find out undergraduate students’ perceptions pertaining to content-based lessons taught in the English language with regard to the topics of curriculum and education. The participants were students from different education majors enrolled in a public Ecuadorian university. In this regard, 171 university students from 4 different majors, including Early Childhood Education, Bilingual Intercultural Education, Special Education and Elementary Education, decided voluntarily to take part in the study by completing an online survey. The group was made up of 34 male students and 137 female students. That is to say, 19.88% (34) were male and 80.12% (137) were female. Furthermore, the surveyed respondents reported to have the following characteristics: 71.93 % (123) of the respondents are between 18 and 21 years old; 22.22 % (38) are between 22 and 23 years old; 3.51 % (6) are between 26 and 29 years old; and 2.34% (4) are between 30 and 34 years old. The two following social economic statuses were reported: 86.55% (148) of the participants come from middle class and 13.45% (23) belong to low class. 82.46% (141) attended public schools, 10,53% (18) attended private schools and 7.02% (12) attended semi-private institutions (which receive funding from the government).

Respondents were also questioned whether English lessons were mandatory at their high schools. The majority of students, that is 95.32% (163), indicated that English was mandatory, whereas only 4.68% (8) reported that it was not compulsory. The number of years that the respondents have studied the English language and their language proficiency levels were also characteristics observed. With regard to the time they have spent studying English, 30.99% (53) declared to have studied English for 13 to 15 years; 20.47% (35), for 10 to 12 years; 14.62% (25), 4 to 6 years; 12.87% (22), for 7 to 9 years; 11.70% (20), for 1 to 3 years; and 9.36% (16), for more than 15 years. Concerning their self-reported English proficiency levels, the majority of students, that is 63.16% (108), were beginners; 35.09% (60) were in an intermediate level; 1.17% (2) were advanced language learners, and 0.58% (1) were native-like speakers.

The administered survey questionnaire consisted of thirteen close-ended items and one open-ended question. It was designed after the authors of the study reviewed the literature associated to the research topic and they used the concepts and theories learned from the reviewed literature in order to come up with the instrument of data collection. Before actual data collection started, the entire survey questionnaire was entered into the LimeSurvey platform. The survey aimed to gather data on several different aspects through the self-report method, such as students’ enjoyment for English language learning, the importance and helpfulness behind learning content from courses taught in English at the university level, the appropriateness about using English as the medium of instruction for a university course regarding curriculum, the positive effects that content-based lessons centered on curriculum taught in English had for the respondents in terms of motivation, confidence, participation, overall academic performance, critical thinking, cognition, and progress, as well as the impact of the delivered lessons on their major English language skills. Additionally, the survey included an open-ended question that prompted the participants to think about how the instructional process of university courses taught in English would help them in their future lives.

After the data were collected, it was analyzed as follows: the information processing was carried out through SPSS 25 and the creation of graphs was done by means of Microsoft Excel 2019. Moreover, the set of qualitative information, gathered through the open-ended question posed to the respondents, was first analyzed by organizing the raw data. Then the information was grouped into major different categories, and afterwards it was interpreted.

RESULTS

Figure 1. Enjoyment for learning the English language.

Source: The authors

With regard to how much the surveyed students enjoy learning the English language, it was found out that 27 (15,79%) of the participants enjoy learning this foreign language a great deal, 54 (31,58%) participants enjoy learning it a lot, 62 (36,26%) of them enjoy English somewhat, 21 (12,28%) enjoy English just a little and 7 (4,09%) students do not enjoy it at all.

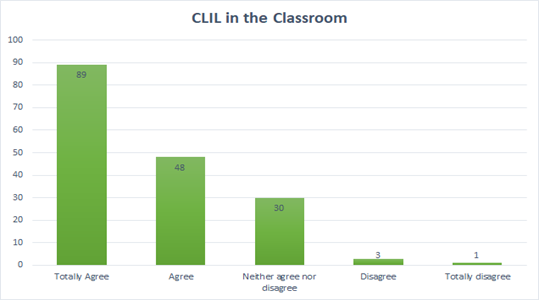

Figure 2. Learning university subjects in English as a way to improve language proficiency.

Source: The authors

With regard to learning university subjects in the English language as a way to improve students’ proficiency level during their undergraduate programs, 89 (52,05%) of the surveyed students totally agree that learning English through university subjects will help them to improve their proficiency level. While 48 (28,07%) students agree, 30 (17,54%) neither agree or disagree, 3 (1,75%) disagree and only 1 (0,58%) totally disagrees.

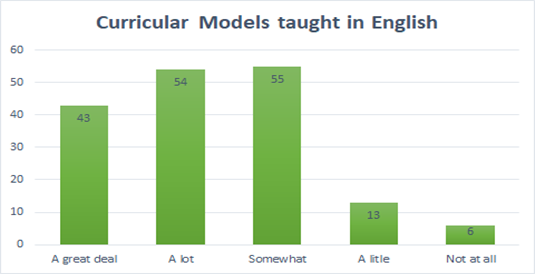

Figure 3. Curricular Models course being taught in English at university.

Source: The authors

In regard to the 171 surveyed students’ perceptions towards the appropriateness of the Curricular Models course being taught in the English language in their majors, 43 (25,15%) of them had a great deal of interest in having this course be taught in the English language. 54 (31,58%) students stated that it was appropriate a lot to study the course in English in their majors. Similarly, 55 (32,26%) mentioned that studying it in English was somewhat appropriate, while 13 (7,60%) claimed it was little appropriate and 6 (3,51%) said it was inappropriate the teaching of it in English.

Figure 4. The effect of class sessions of the Curricular Models course on participants’ academic training.

Source: The authors

With regard to the positive effect of the Curricular Models course on academic training, from the total surveyed students, 53 (30,99%) claimed the course sessions had a great deal of positive effect, and 87 (50,88%) mentioned the sessions positively impacted them a lot. Whereas, 25 (14,62%) students considered the sessions somewhat contributed to their academic training, and 6 (3,51%) believe they helped them just a little.

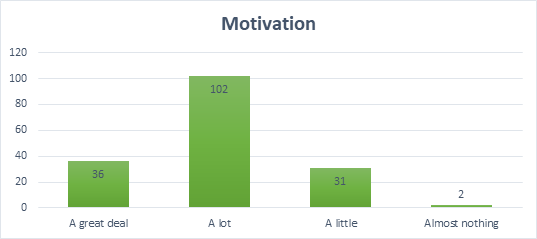

Figure 5. The effect of class sessions of the Curricular Models course on participants’ motivation.

Source: The authors

In terms of the positive effect of class sessions of the Curricular Models course on the surveyed students’ motivation, 36 (21,05%) students mentioned the course sessions had a great deal of positive effect. In the same light, 102 (59,65%) stated the sessions impacted positively their motivation a lot, while 31 (18,13%) said the positive effect was a little and 2 (1,17%) mentioned there was almost no beneficial effect.

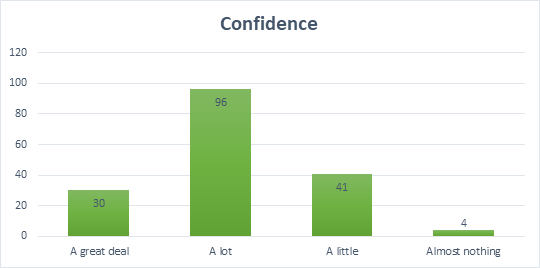

Figure 6. The effect of class sessions of the Curricular Model course on participants’ confidence level.

Source: The authors

With regard to the students’ perceptions about the extent in which the Curricular Models course had a positive effect on their confidence, from the total surveyed students, 30 (17,54%) of them mentioned the course lessons had a great deal of positive effect, and 96 (56,14%) students believed the sessions impacted them positively a lot. On the other hand, 41 (23,98%) said the positive effect was a little and 4 (2,34%) indicated there was almost no favorable effect.

Figure 7. The effect of class sessions of the Curricular Models course on participants’ class participation.

Source: The authors

In terms of the positive effect of class sessions of the Curricular Models course on the students’ participation, 26 (15,20%) students indicated that the course sessions had a great deal of positive effect, and 83 (48,54%) students said the sessions impacted them positively a lot. However, 60 (35,09%) students mentioned the favorable effect was a little, and 2 (1,17%) students said there was almost no beneficial effect.

Figure 8. The effect of class sessions of the Curricular Models course on participants’ performance

Source: The authors

Concerning to what extent the participants believed that the class sessions of the Curricular Models course had a positive effect on their performance, 28 (16,37%) students reported the course sessions had a great deal of positive effect, 103 (60,23%) replied the sessions impacted them positively a lot, 39 (22,81%) stated the beneficial impact was a little, and only 1 (2,34%) indicated there was almost no favorable effect.

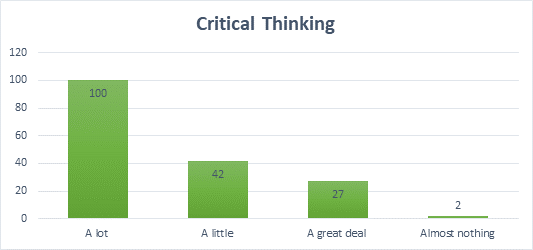

Figure 9. The influence of class sessions of the Curricular Models course on participants’ development of critical thinking.

Source: The authors

Regarding to what extent the participants perceived that the class sessions of the Curricular Models course had a positive influence on their development of critical thinking, 27 (15,79%) students claimed the course sessions had a great deal of positive influence, 100 (58,48%) reported the sessions influenced them positively a lot, 42 (24,56%) stated the positive influence was a little, and 2 (1,17%) indicated there was almost no beneficial influence.

|

|

Figure 10. The influence of class sessions of the Curricular Models course on participants’ cognition.

Source: The authors

Relating to what extent the participants viewed that the class sessions of the Curricular Models course had a positive influence on their cognition, 21 (12,28%) students stated the course sessions had a great deal of positive influence, 112 (65,50%) students indicated the sessions influenced them positively a lot, 37 (21,64%) reported that the positive influence was a little, and 1 (0,58%) claimed there was almost no good influence.

Figure 11. The influence of class sessions of the Curricular Models course on participants’ progress.

Source: The authors

Concerning to what extent the surveyed students believed that the class sessions of the Curricular Models course had a positive influence on their progress of their English learning, 28 (16,37%) indicated the course sessions had a great deal of positive or beneficial influence, 104 (60,82%) mentioned the sessions impacted them positively a lot, 38 (22,22%) reported the positive influence was a little, and 1 (0,58%) replied there was almost no positive influence.

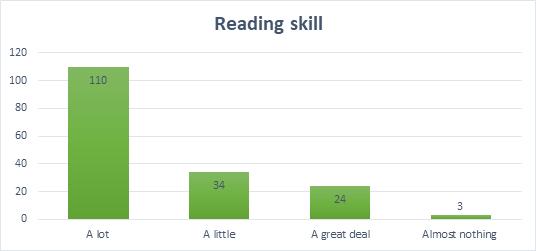

Figure 12. Developing English language skills through the Curricular Models course.

Source: The authors

In regard to what extent the students believed that the class sessions of the Curricular Models course helped them develop their English reading skill, 24 (14,04%) students reported the course sessions helped them a great deal to develop the aforementioned skill, 110 (64,33%) mentioned the sessions helped them a lot, 34 (19,88%) replied they helped them a little, and 3 (1,75%) stated they helped them almost nothing.

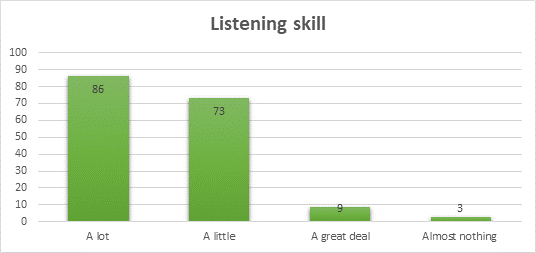

Figure 13. Developing English language skills through the Curricular Models course.

Source: The authors

In regard to what extent the students believed that the class sessions of the Curricular Models course helped them to develop their English listening skill, 9 (5,26%) students stated the course sessions helped them a great deal to develop the aforementioned skill, 86 (50,29%) claimed the sessions helped them a lot, 73 (42,69%) indicated they helped them a little, and 3 (1,75%) mentioned they helped them almost nothing.

In addition to the results drawn from the above close-ended questions of the administered survey, the participants were asked to think and explain how learning undergraduate subjects in the English language would help them in their future personal and professional lives. In order to analyze these responses, the qualitative software NVivo 12 was employed. The open-ended question was administered in the participants’ native language (Spanish), in order to obtain more in-depth responses, in this regard, the NVivo software was programmed to analyze the data in the same language. The program recognized 169 responses in which 49 of the participants stated that learning a subject in English at university can have a very positive impact on their future lives. From the 169 analyzed responses, 116 of them referred to the broad idea that learning undergraduate subjects in the English language can have a moderate positive impact in their future lives. On the other hand, 4 of the participants responded that it will not have a negative impact on their lives, but that it was complex for them to learn another subject in a foreign language, such as English. Finally, none of the participants mentioned that learning an undergraduate subject in the English language will have a negative impact on their future lives.

Through a thorough analysis of the responses provided for the posed open-ended question, the below major categories (Table 1) were identified and they focus on the different ways learning a subject in English will help university students in their future lives.

Table 1

Categories and evidence from the raw data

|

Categories |

Evidence from the raw data (e.g. extracts of responses or complete answers provided by the participants that exemplify the targeted categories). |

|

Better future job opportunities |

a. Porque te permitirán desenvolverte de una mejor manera, podrás hablar sin ningún tipo de dificultad y estaremos preparados para cualquier tipo de trabajos. b. Para tener mejores oportunidades de interacción con las personas en el lugar de trabajo o en el país que ejerza la carrera. c. El inglés es un lenguaje universal que abre puertas y oportunidades tanto laborales como personales, por lo cual, creo que nos ayuda a mejorar nuestro currículum docente y la vez nos brinda muchas oportunidades. más. Learning undergraduate subjects in English will be useful because: a. These subjects will allow us to develop in a better way, we will be able to speak without any type of difficulty and we will be prepared for any type of work. b. It will help to have better opportunities for interacting with people in the workplace or in the country where we are working. c. English is a universal language that opens doors and opportunities, for both, work and personal activities, which is why, I believe that it helps us to improve our teaching curriculum and at the same time offers us many more opportunities.

|

|

Work performance |

a. Me ayudará porque tendré un mejor manejo de la lengua, además de aprender ya he adquirido la habilidad de entender a un maestro cuando dicta una clase en este idioma, también podré aplicarlo cuando en mis prácticas o ya en ejercicio de mi profesión tenga un niño o niña extranjero podré ayudarle a entender de una mejor manera el contenido. b. El idioma inglés es muy importante ya que nos abre oportunidades en lo laboral y personal, es preciso tener el conocimiento en los dos idiomas para desempeñarnos como docentes investigadores.

c. Ya que la lengua es extranjera y se habla por todos los países se considera de mucha importancia aprender de esta manera ya que la asignatura de “Modelos Curriculares” es fundamental para un docente. d. Ayudando a tener un mejor desempeño laboral, al igual que mantener un mejor rango. e. Esto me ayudará para poder ir desarrollando diferentes textos en otro idioma, esto quiere decir que me ayudaría para desenvolverme de mejor manera dentro del ámbito laboral. Learning undergraduate subjects in English will be useful because: a. It will help me because I will have a better command of the language, in addition to learning it, I have already acquired the ability to understand a teacher when he teaches a class in this language, I will also be able to apply it when I have a foreign child in my pre professional practicum or already practicing my profession, I will be able to help them understand the content in a better way. b. The English language is very important since it opens up opportunities for us at work and in personal activities, it is necessary to have knowledge in both languages to work as teacher-researchers. c. Since the language is foreign and is spoken by all countries, it is considered very important to learn in this way since Curricular Models are essential for a teacher. d. Helping to have a better job performance, as well as maintaining a better rank inside the workplace. e. This will help me to be able to develop different texts in another language, this means that it would help me to develop better in the workplace.

|

|

Effective overall language acquisition |

a. Para continuar mejorando mi nivel de inglés y su comprensión b. Yo creo que la fluidez del idioma avanzaría de mejor manera, permitiendo a los estudiantes poder dominarlo c. Me ayudaría de manera significativa porque me sabría desenvolver de mejor manera en una nueva lengua. Learning undergraduate subjects in English will be useful because: a. It will help me to continue improving my level of English and its understanding. b. I believe that language fluency would advance in a better way, allowing students to master it. c. It would help me significantly because I would know how to better develop myself in a new language.

|

|

Oral and written communication |

a. Es de mucha ayuda para comunicarnos con distintas personas b. Es lo más importante, sabemos que estamos en una sociedad llena de personas que hablan inglés, además de la comunicación es esencial en el trabajo y las oportunidades para viajar y trabajar. c. Yo creo que me ayudaría a desenvolverme mucho mejor en lo que es la lengua de inglés tanto en lo escrito y oral. d. Considero que al ser la materia dictada en inglés existe un poco de complejidad, pero es bueno aceptar retos en la vida, esto nos ayudará para un futuro tener un buen desempeño y tener un buen dialecto en la lengua inglesa debido a que es de gran importancia al momento de la interacción con otras personas. Learning undergraduate subjects in English will be useful because: a. It is very helpful to communicate with different people. b. It is of utmost importance, we know that we are in a society full of people who speak English, Communication is essential at work and for opportunities to travel and work. c. I think it would help me to develop much better in the English language, both in written and oral. d. I think that the subject taught in English is a bit complex, but it is good to accept challenges in life, this will help us to have a good performance and have a good dialect in the English language in the future because it is of great importance at the moment of interacting with other people.

|

|

Academic aspirations |

a. Como futuros docentes considero que deberíamos de saber de todo un poco, el inglés es una lengua importante que nos ayudará a comunicarnos de mejor manera y entender textos para así dialogarlos de manera crítica. b. Es muy importante, ya que la materia al ser en otro idioma era interesante y nos motivaba a tratar de analizar textos junto con nuestro docente, sería bueno que se siga llevando a cabo de esta manera que no solo se aprende modelos curriculares sino también el idioma inglés. c. Es de mucha ayuda, ya que si queremos realizar una maestría en otro país se necesita hablar, entender y escribir en ese idioma. Inglés es el más dominante a nivel mundial, de igual manera para poder graduarse se necesita un nivel base de inglés. d. Lo considero muy bueno debido a que nos ayuda a aprender mucho el inglés, a más de eso nos sirve para poder realizar estudios en un país extranjero o auto educarnos con libros o textos en inglés. e. Considero que el aprendizaje de un idioma diferente es totalmente innovador, puesto que, nos indica nuevas maneras de manejar el inglés y nos prepara para poder realizar estudios posteriores en diferentes instituciones, además, podemos incluir estos aprendizajes a las generaciones siguientes, lo cual será de gran apoyo en nuestra vida diaria y de los demás. f. También puede ayudarme cuando desee hacer una maestría o seguir mis estudios en otro país donde es necesario saber inglés. Learning undergraduate subjects in English will be useful because: a. As future teachers, I think that we should know a little about everything. English is an important language that will help us to communicate better and understand texts in order to dialogue critically. b. It is very important, since the subject is being taught in another language and it was interesting and motivated us to try to analyze texts together with our teacher. It would be good if it continues to be carried out in this way, because we don’t only learn curricular models, but also the English language. c. It is very helpful, since if we want to do a master's degree in another country, we need to speak, understand and write in that language. English is the most dominant language in the world, and in order to graduate we need a basic level of English. d. I consider it very good because it helps us to learn English a lot, more than that, it will help us to study in a foreign country or educate ourselves with books or texts in English. e. I consider that the learning of a different language is totally innovative, since it indicates new ways of handling English and prepares us to be able to carry out further studies in different institutions. Furthermore, we can include this learning to the following generations, which will be of great support in our daily life. f. It can also help me when I want to do a master's degree or continue my studies in another country where it is necessary to know English.

|

|

Effects on personal life |

a. Es muy importante debido a que nos permitirá enseñar a los niños en inglés y así ayudarles a que se vayan acostumbrando a este idioma. b. Considero que esto será de gran ayuda para la vida en general. c. Para tener más oportunidades de trabajo y sobre todo de conocimientos, como también en mi vida personal aporta el idioma inglés ya que en un futuro si viajo a países extranjeros no será difícil entender su idioma. Learning undergraduate subjects in English will be useful because: a. It will allow us to teach children in English and thus help them to get used to this language. b. I think this will be of great help in life in general. c. In order to have more job opportunities and above all, knowledge, as well as in my personal life, it contributes to my language since in the future if I travel to foreign countries it will not be difficult to understand its language.

|

|

Stress release |

a. Si, ya que se emplea mejor el lenguaje, y también se estudia en la misma generando mayor entendimiento de las asignaturas y temas dados, la pérdida de miedo por hablar en inglés o realizar tareas en el idioma extranjero. Learning undergraduate subjects in English will be useful because language is applied in a better way and we also study in it and that generates a greater understanding of the subjects given, the loss of fear for speaking in English, and a better carried out tasks in the foreign language. |

Those extracts are the ones with a higher incidence and a high percentage of repetition. In this regard respondents consider that the mastery of the English language will have a variety of benefits in their in-service performance as future classroom teachers. They also mentioned that the language acquisition will be a lot easier, and this will benefit the way they communicate with other individuals. Furthermore, apart from the job opportunities and the ease in communication that they may encounter in the future, they also mentioned that learning a subject in English will contribute to their academic aspirations. It was indicated that learning the target language through courses taught in English at university would help them to pursue and complete master’s programs more effectively in the future. It is worth mentioning that CLIL does not only have academic effects, but the participants also mentioned important additional facts, such as personal goal impacts, travels and even stress release.

DISCUSSION

According to the students' likings, it seems there are mixed feelings towards the English Language. The findings agree with Tsuchiya and Perez (2015) who addressed concerns and difficulties in implementation of CLIL at universities due to students' insufficient English competence to completely understand subjects. However, similar results to Vergara, Lopez, Macea, and de la Rosa (2016) where students improved their proficiency in the language were yielded, as evidenced by the fact that most learners agree that learning Curriculum Models in English helped them with their proficiency in the target language.

The results comply with Martin de Lama's (2015) words which stated that higher education and post-graduate students have a positive view of CLIL after integrating the learning of English as a foreign language into the curriculum of other content areas. This study shows that students feel the implementation of another subject in English as appropriate from students' perspectives and it also helps them with their training. Further, as Pladevall-Ballester (2018) suggested, students' motivation increased to learn English through the implementation of CLIL.

The outcomes of this study are in line with Lou and Xu (2016), CBI and CLIL could improve the level of English language applied ability of non-English-majored undergraduate students in their English learning. The results pointed out a raise in all class sessions aspects. Most students perceived CLIL helped them in their confidence towards the subject and the target language. Moreover, most students feel their participation, performance, critical thinking, and overall progress perceived a greater impact by learning the subject in English.

In terms of skills development, the majority of the learners stated that the class sessions of the Curricular Models course helped them develop their English reading skill as well as their listening skill. Even though these perceptions come from students, they concur with Guadamillas (2017) perceptions from teachers believing that CLIL is useful and that it is valued when given the opportunity to apply in classrooms. Nevertheless, the skill that students mainly agree upon is reading.

Two matters that need to be kept in mind regarding the results are: the parameters teachers used to plan their classes considering the three dimensions of this approach (Argudo, Abad, Fajardo-Dack & Cabrera, 2018) and the fact that learners’ satisfaction with the CLIL approach could be affected by levels of language proficiency (Yang, 2016). Since this study mainly focused on the students' perceptions on CLIL, those aspects were not included during the research. Those perception results from the learners that did not consider CLIL effective in many of the questions from the survey may be influenced by those two factors. Consequently, as Mcdougald (2017) suggested, few firm conclusions can be drawn in this research field.

It can be drawn from the open-ended question that students consider that learning subjects through CLIL will have positive effect in their future academic fields. None of the learners see this as a disadvantage. Keeping in mind that for second language (L2) CBI/CLIL can be challenging since they must pay attention to the language and content (Vergara et al., 2016), it is clear that the students feel that this method will provide better future job opportunities, help in their work performance, ease language acquisition, improve their communication competence, and contribute to their academic aspirations.

CONCLUSIONS

Language acquisition is conceived in a more natural way which can be a notable advantage of applying CLIL in the classroom. Through content language instruction, teachers and learners are prompted to study terminologies that facilitate a better understanding of subject matter, which enhances the acquisition of the target language. According to the respondents’ viewpoints, having a more effective mastery of the English language it assures greater opportunities, even though, this foreign language is not their main field of study at university.

Using English as a foreign language as a medium of instruction for subjects or courses is helpful and interesting to university students. Education majors can have positive experiences with their English language learning through different instructional activities that are of their interest and systematically focus on their program of study, such as topics discussed in English related to key education-related themes, such as educational philosophies, curriculum design, curriculum development stages, approaches to curriculum and curriculum models.

Designing and implementing content-based lessons in the English language have a positive impact on the development of critical thinking and cognition among university students. In this respect, students are able to become more aware of their own language learning and gain a better understanding of key information by employing different mental processes. By engaging in constant reasoning, decision making, evaluating and problem solving in a foreign language, students at the university level have greater opportunities to improve their target language and be equipped with essential knowledge and tools associated to course content in an effective manner.

CLIL-oriented lessons enable the connection between language development and specific course content, which subsequently increases student’s motivation towards both of them. While focusing primarily on content, CLIL simultaneously contributes to build confidence in the language skills, meaning on a notable upturn of development in academic, professional and personal fields.

REFERENCES

Admiraal, W., Westhoff, G., & De Bot, K. (2006). Evaluation of bilingual secondary education in the Netherlands: Students' language proficiency in English. Educational research and Evaluation, 12(1), 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610500392160

Argudo, J., Abad, M., Fajardo-Dack, T. & Cabrera, P. (2018). Analyzing a pre-service EFL program through the lenses of the CLIL approach at the University of Cuenca-Ecuador. LACLIL, 11(1), 65-86. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.4

Cenoz, J. (2015). Content-based instruction and content and language integrated learning: the same or different? Language, Culture and Curriculum, 28(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2014.1000922

Coyle, D. (2007). Content and language integrated learning: Towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogy. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb459.0

Coyle, D., Hood, P. & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Google Scholar. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.01.001

De Graaff, R., Jan Koopman, G., Anikina, Y., & Westhoff, G. (2007). An observation tool for effective L2 pedagogy in content and language integrated learning (CLIL). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), 603-624. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb462.0

Georgiou, S. (2012). Reviewing the puzzle of CLIL [Special issue, October]. ELT Journal, 66(4), 495‒504. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccs047

Guadamillas, M. (2017). Trainee primary-school teachers’ perceptions on CLIL instruction and assessment in universities: A case study. Acta Scientiarum. Education, 39 (1). 41-53. https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v39i1.32901

Kang, A. (2007). How to better serve EFL college learners in CBI courses. English Teaching-Anseonggun-, 62(3), 69. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.62.3.200709.69

Koopman, G. J., Skeet, J., & de Graaff, R. (2014). Exploring content teachers' knowledge of language pedagogy: A report on a small-scale research project in a Dutch CLIL context. The Language Learning Journal, 42(2), 123-136. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2014.889974

Llinares, A., Morton, T., & Whittaker, R. (2012). The roles of language in CLIL. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lou, Y. G., & Xu, P. (2016). Effects of Content-Based Instruction to Non-English-Major Undergraduates English Teaching with Internet-Based Language Laboratory Support. Creative Education, 7. 596-603. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.74062

Mart, C. (2019). A comparison of form-focused, content-based and mixed approaches to literature-based instruction to develop learners´ speaking skills. Cogent Education, 6. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1660526

Martín de Lama, M. A. (2015). Making the match between content and foreign language: A case study on university students’ opinions towards CLIL. Higher Learning Research Communications, 5(1), 29-46. https://doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.v5i1.232

McDougald, J.S. (2017). Language and content in higher education. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 10(1), 9-16. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2017.10.1.1

Pérez-Cañado, M. (2012). CLIL Research in Europe: Past, Present, and Future. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15(3), 315‒341. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2011.630064

Pladevall-Ballester, E. (2018). A longitudinal study of primary school EFL learning motivation in CLIL and non-CLIL settings. Language Teaching Research, 136216881876587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818765877

Reiter, B. (2017). Teoría y metodología de la investigación exploratoria en ciencias sociales. Human Journals, 5 (4), 130-150.

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.12691/jll-2-1-1

Sato, S., Hasegawa, A., Kumagai, Y., & Kamiyoshi, U. (2017). Content-based Instruction (CBI) for the Social Future: A Recommendation for Critical Content-Based Language Instruction (CCBI). L2 Journal, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.5070/l29334164

Stoller F.L. (2008). Content‐Based Instruction. In: Hornberger N.H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30424-3_89

Tsuchiya, K., & Pérez Murillo, M. D. (2015). Comparing the language policies and the students’ perceptions of CLIL in tertiary education in Spain and Japan, 8(1), 25-35. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2014.8.1.3

Vergara, L., López, J., Macea, J., & de la Rosa, A. (2016). Content-Based Instruction in Colombian Universities. Adelante Ahead Revista Institucional, (7), 55-63.

Verspoor, M., de Bot, K., & Xu, X. (2015). The effects of English bilingual education in the Netherlands. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 3(1), 4-27. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.3.1.01ver

Waller, T. A. (2018). Content-Based Instruction. The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0168

Yang, W. (2016). An investigation of learning efficacy, management difficulties and improvements in tertiary CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) programmes in Taiwan: A survey of stakeholder perspectives. LACIJL, 9(1), 64-109. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2016.9.1.4