Desarrollar la pronunciación del inglés de estudiantes de secundaria mediante el uso de videos educativos en la clase

Developing middle school students’ English pronunciation using educational videos in the classroom

Lorena Reinoso Illescas1, Esteban Heras Urgiles2

1.* Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador. Email: lorena.reinosoi@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0070-6594

2. Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador. Email: esteban.heras@ucuenca.edu.ec ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7330-3721

Recibido: 12/01/2021

Aceptado: 24/03/2021

Como Citar: Reinoso Illescas, L., & Heras Urgiles, E. (2021). Desarrollar la pronunciación del inglés de estudiantes de secundaria mediante el uso de videos educativos en la clase. Revista Publicando, 8(29), 54-64. https://doi.org/10.51528/rp.vol8.id2173

RESUMEN

Este estudio examina la extensión en la cual, estudiantes de secundaria mejoraron su pronunciación mediante el uso de videos educativos además recoge sus percepciones sobre el uso de esta técnica. Este estudio se llevó acabo en una institución educativa pública en la ciudad del Cuenca- Ecuador. Sesenta y Cinco estudiantes de noveno grado participaron: 33 estudiantes (15 varones y 18 mujeres) fueron parte del grupo de intervención y 32 estudiantes (15 varones y 17 mujeres) fueron parte del grupo de control. Para este estudio se utilizó un método mixto, reuniendo datos cualitativos y cuantitativos. Los estudiantes tomaron un pre y post test que fueron lecturas en voz alta para evaluar su pronunciación. Al final del estudio, los estudiantes del grupo de intervención respondieron un cuestionario de preguntas abiertas acerca del uso de videos en clase. También, durante las 10 semanas de tratamiento, el grupo de intervención recibió clases con el uso regular de videos, mientras que el grupo de control recibió clases usuales con la investigadora, en este grupo no fueron usados videos. Los resultados finales mostraron que las percepciones del grupo de intervención con respecto al uso de videos en clase, fueron en su mayoría positivas; consideraban los videos útiles, ya que escuchaban la pronunciación correcta, observaban los movimientos faciales lo que les permitía entender mejor la pronunciación. Finalmente, el análisis estadístico de los datos del pre y post test, demostró que hubo una mejora en la pronunciación del grupo de intervención.

Palabras clave: Pronunciación, videos, percepciones, lectura, intervención

ABSTRACT

This study examines the extent to which middle school students improved their pronunciation through the use of educational videos and what their perceptions were about this technique. The study was carried out at a public educational institution in Cuenca – Ecuador. Sixty-five ninth-graders participated: 33 students (15 boys and 18 girls) were part of the intervention group, and 32 students (15 boys and 17 girls) were part of the control group. The study used a mixed-method approach, so both quantitative and qualitative data were collected. The students took a pre- and a post-test based on a reading aloud activity to measure their level of pronunciation. Furthermore, at the end of the study, they were invited to complete a questionnaire with open-ended questions about the use of videos in class. During the ten weeks of the treatment, the intervention group received classes that included the regular use of videos, while the control group received their usual classes with the researcher; no videos were used at all. The final results showed that students’ perceptions in the intervention group regarding the use of videos in the class were mostly positive; they considered videos useful for the improvement of pronunciation because they heard the correct pronunciation and could observe facial movements, which helped to acquire better pronunciation. Further, the statistical analysis of the scores given in the pre- and post-test by both evaluators (researcher and inter-rater) showed that there was an improvement in the students’ pronunciation skills in the intervention group.

Keywords: Pronunciation, videos, perceptions, reading, intervention

INTRODUCTION

English has been a mandatory subject in primary and secondary schools in our country, Ecuador, since 2016 based on a government ministerial agreement (Acuerdo Ministerial Nº 0052-14). It was one of the efforts made by the government to improve the English comprehension and proficiency level of secondary school students in Ecuador. Nevertheless, some studies, such as EF EPI-s (2017) carried out by Education First, Calle et al., (2012), and most recently, Ortega and Fernández (2017) showed that the English language proficiency levels of secondary school students are low. Additionally, the studies demonstrate that one of the reasons for this low level is that teachers use traditional teaching strategies where speaking and pronunciation are not promoted and are often limited to simple question and answer exchanges (teacher – students) (Calle et al., 2012).

Furthermore, The British Council (2015) carried out a study in several Latin American countries, including Ecuador, to find out about the English language proficiency of students at primary, secondary, and tertiary educational levels. The results showed that Ecuadorian high school students were at a low level in terms of speaking English. Also, Argudo et al., (2018) mentioned in their study that 52% of pre-service teachers in the fourth semester at a public university are at A1 and A2 levels of English, which, considering their academic level (fourth semester), demonstrates a low level of proficiency. The data also confirmed that students consider speaking a hard skill to acquire. Moreover, a recent study accomplished by Education First EF EPIs (2019) also found poor English skills at all levels. They tested groups of students at secondary (10th year) and preparatory (3rd of Bachillerato) levels and found that most of them performed between pre-A1 and A1 levels according to the Common European Framework of Reference. These low levels of proficiency were confirmed by Calle et al. (2012) as well. These low language proficiency results must be overcome to achieve what is determined in the updated version of the National Curriculum Guidelines for Subnivel Superior (NCGSS) (Ministerio de Educación, 2019), that states that the students’ learning has to focus on engaging in “purposeful communicative interaction” (p. 415). It is to be noted that Subnivel Superior (namely, 8th, 9th, and 10th grades) are the equivalent to secondary school in the United States.

According to the NCGSS, by the end of the 9th grade, students must acquire an A1.2 English proficiency level, which is explained in detail in the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). This level describes that students must “interact in a simple way … rather than relying purely on a very finite rehearsed, lexically organized repertoire of situation-specific phrases” (p. 35). Indeed, ninth-grade students are supposed to have accomplished the A1.2 level, but based on the information from the aforementioned studies, students in Ecuador generally have a low English proficiency level, especially in speaking.

Considering this low language proficiency level, the present study focused on the use of educational videos in class and intended to improve students’ pronunciation, its components, intelligibility - which is essential in order to gain communicative competence, and intonation-stress, which is a suprasegmental component. It is worth mentioning that pronunciation is considered as “an integral part of English language learning (…) so it means it is an important part of gaining communicative competence” (Gilakjani & Sabouri, 2016, p. 196). Setter and Jenkins (2004) also emphasize that pronunciation “plays a vital role in successful communication both productively and receptively” (p. 2).

Even though pronunciation is important for communicative competence, it is often ignored in EFL classes. Gilbert (as cited in Gilakjani & Sabouri, 2016) mentions two reasons why pronunciation is neglected: 1) the lack of time for teaching pronunciation; and 2) psychological factors, which show that learners are insecure about their English pronunciation. Additionally, Gilakjani and Sabouri (2016) indicate that pronunciation has not been considered an important aspect to be included in the curriculum design of different universities, and this is true for Ecuador as well. A thorough examination of the National Curriculum Guidelines for Subnivel Superior makes it clear that pronunciation is only mentioned as part of potential interactions; it says, “the speaker must have good pronunciation, stress, and intonation to be understood.” Strategies to develop pronunciation and any other components are not specified in it. Because of this, we have to look for different strategies to try to find a solution to this problem and try to teach pronunciation in our EFL classes. One of the techniques that has provided good results in terms of teaching and learning pronunciation is the use of videos in the classroom (Cundell, 2008). Therefore, in the present project, it was investigated ninth-grade students of a public institution would also benefit from this technique when intending to improve their pronunciation of English, which leads to progress in speaking, too. Information about their perceptions regarding the use of videos in the classroom was also gathered and analyzed. Moreover, additional information about the importance of pronunciation and the use of videos in class is also presented.

Pronunciation

Gilakjani (2016) indicates that when a listener can understand the speaker without much difficulty, the speaker can be assumed to have adequate pronunciation. Yates and Zielinski (2009) explain that pronunciation refers to how humans produce sounds to create meaning when they speak, where the segmental and suprasegmental aspects of speaking are also included. Moreover, Moedjito (2016) claims that poor pronunciation might hinder oral communication across cultures. Besides, Harmer (as cited in Gilakjani, 2017) remarks that “the first thing native speakers notice is pronunciation” (p. 3). He also mentions that pronunciation is an indispensable component of communication and that if a person does not pronounce words correctly, that person does not communicate successfully. Furthermore, Gilakjani (2017) explains that pronunciation is essential for communicative competence and emphasizes the importance of segmental and suprasegmental units of speech, too. Likewise, Setter and Jenkins (as cited in Moedjito, 2016, p. 30) state that pronunciation “plays a vital role in successful communication both productively and receptively.”

Is it important to teach pronunciation in the classroom? The answer to this question is obviously “yes”. Tejeda and Santos (2014) suggest that instructors should pay special attention to instruction in pronunciation because if pronunciation mistakes are not corrected within an appropriate period of time, these mistakes could be fossilized in the students’ lexicon. Based on the results of different studies, Jenkins and Macdonald (as cited in Moedjito, 2016) claim that “good pronunciation should be an important goal in an EFL classroom” (p. 31). Moedjito (2016) also found that teachers and students perceive pronunciation as a fundamental part of language. Finally, Morley (1991) recommends that pronunciation must be integrated into the second language curriculum as a necessary part of communication.

Use of Videos

To improve the participants' pronunciation, educational videos downloaded from various YouTube channels were used. Several studies demonstrate that videos are useful resources for improving pronunciation (and other skills, too) in the target language. For example, Cundell (as cited in Yassaei, n.d) contends that videos can be an important tool and should be integrated into language classes because they provide the “visual representation of abstract concepts” (p. 13). Wilson (as cited in Yasin, Mustafa, & Permatasari, 2018) emphasizes that videos are “contextual, show body language, and help students with short attention spans” (p. 92). Berk (2009) stresses that the use of videos can help to accomplish different learning outcomes, such as capturing students’ attention, focusing on students’ concentration, and generating interest in class. Additionally, the use of multimedia learning and videos in speaking classes enhances students’ pronunciation and motivation at secondary and university levels when learning the target language (Ratnawati & Faridah, 2017; Park & Jung, 2016). Chen (2011) and BavaHarji et al. (2014) conducted studies whose results confirmed that captioned videos helped students to improve their oral skills and they enjoyed using these resources. It was also found that the use of videos helped to strengthen the vocabulary of fifth graders in an EFL setting (Celis Nova et al., 2017). Furthermore, Alwehaibi (2015) demonstrated that the use of YouTube technology had positive effects on the participants and also enhanced the learning process in several ways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research study used a mixed-method approach to collect qualitative and quantitative data. Also, it should be noted that a non-probability convenience sampling technique was used. The participants were chosen because they were easy to contact. Finally, this research followed the principles of a quasi-experimental research design.

Participants and Setting

Altogether 65 ninth graders of the afternoon shift of a public school in Cuenca took part in this study; 33 students (15 boys and 18 girls) were part of the intervention group and 32 students (15 boys and 17 girls) were part of the control group. The participants were 13 to 14 years old.

Instruments

In this study, pre- and post-tests were used to measure the pronunciation level of students before and after the treatment. The test was a reading aloud activity that was recorded by the researcher, one student at a time. The pre-test was a piece of reading taken from the ninth grade English book provided by the Ministry of Education (Nuñez, 2015) while the post-test was a text created by the researcher drawing on the information from the videos used in class during the treatment. Even though the pre- and post-tests were different in content, the level of difficulty, vocabulary, and the time, which was 2 to 4 minutes talk, was kept the same. As this study aimed at the improvement of pronunciation, with intelligibility and intonation-stress the measured components, an adapted version of a rubric created by Ramanarayanan, Lange, Evanini, Molloy, and Suendermann-Oeft (2017) was used. Since the proposed strategy was to use educational videos in class, the students watched videos three times a week over 10 weeks. The researcher carefully chose and edited the videos from the video platform YouTube, following Berk (2009) criteria. The first criterion concerns socio-demographic characteristics, which means that the teachers should know their students well, and it is therefore assumed that they can choose the most appropriate videos to show to them. The second consideration is the possible offensiveness of a video, which is important to contemplate because the content needs to be "acceptable"; if students find the video offensive, they can feel uncomfortable, which may affect their learning. The third aspect to consider is the structure of the video, the length, the context, actions/visual cues, and the number of characters. Regarding the length of the videos, Richards and Renadya (2002) suggest that the length of the videos to be used in class should be from 3 to 5 minutes instead of longer sequences, which could result in the students losing attention. Indeed, the videos used in this study were between 2:30 and 4:00 minutes long.

Procedure

Before starting the research process, permission from the authorities of the school was obtained to carry out the study at the institution. Furthermore, the researcher explained all the study details to the participants and their parents; they signed an informed consent form approving their children’s participation and the participants also signed the relevant form agreeing to participate. Additionally, participants and their parents were also informed that when presenting and analyzing the results of this study, no names were going to be used, and that each student was going to be assigned a code, which consists of the letter of the course, the first letter of the last name, and the first letter of the given name.

Additionally, the students’ class schedule, which was 5 English classes of 40 minutes per week, determined the frequency with which the proposed technique was employed.

While working on the treatment, the researcher was in charge of the two groups (intervention and control) covering units 5 and 6 of the English course book. The grammar point of both units was the past simple (verb ‘to be’ and regular and irregular verbs). The topics covered dealt with famous people in the past and descriptions of past experiences. During the treatment, the teaching methods and techniques used with the control group were the ones that the researcher usually applies in her teaching practice, such as doing the exercises in the course book, gap fill activities, individual and group work, listening to short audios, hands-on activities, etc. As for the intervention group, before presenting the videos on Monday and Tuesday, the researcher introduced the topic of the lesson, the grammar point, and the vocabulary. Then, on Wednesday students were given the transcript of the video and some examples of the grammar point, they watched the video twice, and they had to recognize the grammar structures in the transcript. On Thursday, the students using the same transcript practiced their pronunciation in four different stages: 1) they only watched the video; 2) the video was played again and they had to follow the transcript; 3) they practiced their pronunciation in pairs by reading the transcript; they had to listen to each other; and 4) they watched the video again to check how they pronounced the words that occurred in it. Finally, on Friday, students watched the same video to refresh pronunciation, grammar, and to complete comprehension question exercises related to the video which included the grammar point. Also, they had to share the answers with the whole class. During this video application period, the researcher gave neither pronunciation instruction nor correction. This procedure followed Celce-Murcia, Brinton, and Goodwing (1996) “intuitive approach”, which exploits the learner’s ability to listen and imitate the sounds and rhythm of the target language without receiving explicit instruction. Finally, an inter-rater, who is a native English speaker, was also involved in this study to evaluate the pre- and post-tests following the suggestion of Karim and Haq (2014), who mention that in the speaking section of the IELTS exam there should be more than one examiner to increase reliability and reduce responsibility from a single rater. This was also applicable to this study because it was a speaking test, and it was necessary to ensure the reliability of results.

RESULTS

As this study gathered quantitative and qualitative data, the quantitative data are presented first; these explore the influence of videos on the participants’ pronunciation, its components, intelligibility, and intonation-stress. These results were processed by the statistical software SPSS 25, and a non-parametric test, U Mann-Whitney was also used for comparing the two groups. Further, the Wilcox test was employed to compare the results before and after the intervention. The considered statistical mean was 5% (p<.05). Finally, as the evaluation of the pre- and post-tests was done by the researcher and the inter-rater evaluator, the results arising from the scores given are presented separately and then are compared.

Spanish speaker (Researcher)

The pre-test results of the pronunciation components, namely, intelligibility and intonation-stress are in a range between 0 and 4. The intervention group showed low scores in both components (MIntellibility =1; SD=0.9; MIntonation =0.4; SD=0.7) and so did the control group (MIntellibility = 0.9; SD=0.9; MIntonation =0.4; SD=0.9). It is, therefore, concluded that no considerable differences were to be found in the results before the intervention. In other words, both groups were more or less at the same level of knowledge and pronunciation skills.

In the post-test, a range between 0 and 4 points was established for each component; intelligibility was the component with a higher score in both groups. Intelligibility was significantly high in the intervention group (M=2.6; SD=0.8) (p<.05), while the control group showed a mean of 1.7 (SD=1.0). In the case of intonation-stress, the intervention group showed a mean of 2.1 (SD=1.0) against a mean of 1.1 points (SD=0.9) of the control group. Table 1 shows significant differences between the two groups in both components of pronunciation after the intervention.

|

Table 1. Comparison of the 2 pronunciation components (intelligibility and intonation/stress) PRE – POST tests between groups (Researcher). |

|||||||

|

|

Intelligibility |

U |

Intonation-Stress |

U |

|||

|

Intervention |

Control |

Intervention |

Control |

||||

|

Pre-test |

Minimum |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.393 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.594 |

|

Maximum |

3.0 |

4.0 |

2.0 |

4.0 |

|||

|

Mean |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|||

|

SD |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

|||

|

Post-test |

Minimum |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.000* |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.000* |

|

Maximum |

4.0 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

|||

|

Mean |

2.6 |

1.7 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

|||

|

SD |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

|||

Note: * (p<.05) Significant difference.

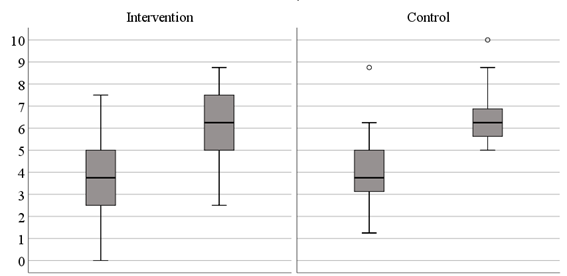

To display the findings above, figure 1 shows the distribution of data for both groups before and after the intervention on a scale from 0 to 10, which corresponds to the Ecuadorian national grading system. Altogether, it was found that both groups increased their pronunciation abilities significantly (p<.05). The intervention group improved by a medium change of 4.05 points and the control group by a medium change of 1.91 points. It was also found that four students in the control group displayed a significantly higher performance than the group average.

Figure 1. Comparison between the 2 groups of the total pronunciation accomplishment (Researcher)

Note: On each side (Intervention and control), left candlestick for total pronunciation pre-test; right candlestick for total pronunciation post-test. By Authors.

Native English Speaker (Inter-rater)

Table 2 shows the results of the pronunciation components before and after the intervention as evaluated by the inter-rater. In both groups, the scores range between 0 and 4 in each component in both stages of the evaluation. In the pre-test, the intelligibility component of both groups (intervention and control) was a mean of 1.5 (SD = 0.8), which means that there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding intonation-stress.

After the intervention, the mean score of intelligibility was 2.7 (SD = 0.8) for the intervention group, while that of the control group was 2.3 (SD = 0.7). Intonation-stress was a weaker component with a mean of 2.2 (SD = 0.8) in the intervention group and 1.7 (SD = 0.6) in the control group.

|

Table 2. Comparison of the 2 pronunciation components (intelligibility and intonation/stress) PRE – POST tests between groups (Inter-rater) |

|||||||

|

|

Intelligibility |

U |

Intonation-Stress |

U |

|||

|

Intervention |

Control |

Intervention |

Control |

||||

|

Pre-test |

Minimum |

0.0 |

0.5 |

0.900 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.989 |

|

Maximum |

3.0 |

4.0 |

2.0 |

3.5 |

|||

|

Mean |

1.5 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|||

|

SD |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

|||

|

Post-test |

Minimum |

0.5 |

1.5 |

0.713 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

0.600 |

|

Maximum |

4.0 |

4.0 |

4.5 |

4.0 |

|||

|

Mean |

2.7 |

2.3 |

2.2 |

1.7 |

|||

|

SD |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

|||

To represent the findings, figure 2 shows the distribution of data for both groups before and after the intervention on a scale from 0 to 10, which corresponds to the Ecuadorian national grading system. We can observe that the control group showed a more homogeneous dispersion of the data than the intervention group. Pronunciation in the pre-test in the intervention group was 4.1 (SD = 1.8) against 6.36 (SD = 1.7) in the post-test. In the control group, in the pre-test, the median score was 3.3 (SD=1.6) while in the post-test it reached 6.4 (SD=1.6). There were minor changes to be found before and after the intervention in both groups (p<.05), namely, an average increase of 2.2 in the intervention group and 2.07 in the control group. Even though the intervention group displays better results, the data are not statistically significantly different from those of the control group (p>.05). The data also demonstrate that the scores given by the native English speaker before the intervention were significantly higher than the scores given by the researcher (p<.05). Furthermore, there was a participant who received significantly higher scores from the inter-rater than all the others in the group.

Figure 2.

Comparison

between the 2 groups of the total pronunciation accomplishment

(Inter-rater)

Note: On each side (Intervention and control), left candlestick for total pronunciation pre-test; right candelstick for total pronunciation post-test. By Authors.

In figure 3, the number of students in both groups who showed positive and negative changes after the treatment as well as the ones who remained at the same level of pronunciation are presented. We can see that even though there were significant differences in the scores given by the two evaluators, with the inter-rater evaluator giving higher scores to the participants, their perceptions were similar in terms of the improvement of both groups.

Figure 3.

Changes between pre and post-test according to the total number of students.

In sum, it can be said that even though there were significant differences between the scores given by the two evaluators, an improvement in the pronunciation performance of the intervention group was found.

Students’ Perceptions

Thirty-three students of the intervention group anonymously and individually answered four questions about the use of videos in class. There were 31 positive responses related to the benefits students perceived they received from videos and also how they felt towards the use of these. Participants mentioned they could see facial movements, and they listened to the correct pronunciation; an extra benefit they mentioned was that the images helped them to understand the context of the video better. Some examples of what they said were:

Student NN "For me, it was good because is a new way of learning while the narrators pronounce the words and move their lips"

Student NN “The video is an example of how people pronounce”

Student NN “I felt good because I correct my pronunciation and accent”

Student NN “I felt good because with the videos we learned the correct pronunciation”

Student NN “I felt good because images helped to understand more about the topic”

As it was mentioned, two participants expressed two negative perceptions about the use of videos in the classroom, they said:

Student NN “I did not feel comfortable because the pronunciation was fast”

Student NN “It was weird because pronunciation was something new”

DISCUSSION

The results of the pre and post-test of this study give information about the extent to which the use of videos influences the improvement of students’ pronunciation. The findings show that there was an improvement in the intervention group. This information is in accordance with Yükselir and Kömür (2017), who claim that the use of videos in class is important and can be highly effective when it comes to improving EFL learners’ speaking ability. Also, Muslem, Mustafa, Rahman, and Usman (2017) demonstrated that the use of video clips with small-group activities improved the speaking skills of young learners in their study. Besides, Davis (1999) also found that the participants’ pronunciation of discrete sounds improved; the author used pronunciation instruction videos in the study.

To find out about the participants’ perceptions regarding the technique applied in this study, the answers of the interview were also analyzed. With the exception of two participants, everyone had positive views about the use of videos in class. The majority mentioned that they could see how the speakers talk, which helped them to learn how to pronounce certain words. This is corroborated by Canning-Wilson (2000), who defines videos as “the selection and sequence of messages in an audio-visual context”, which include different settings, verbal and non-verbal signals, and paralinguistic features. Also, some participants felt motivated to improve their pronunciation, and indicated that the use of videos was a new technique for them, and they could acquire more information because the classes became more interesting. This is also endorsed by Bravo et al. (2011), who point out that videos increase students’ motivation and enhance students’ interest in the subject and facilitates the transmission of information. Indeed, Cabrera, Espinoza, Solano, and Ulehlova (2017) emphasize that students find videos motivating and engaging because they help them to learn better in an interactive manner. Additionally, Isiaka (2007) states that videos help students to experience new things while Çakir (2006) underlines that learners find videos fun and stimulating. Also, videos boost positive attitudes as well as promote success in learning and heighten the confidence of learners (Brewster et al. as cited in Muslem et al., 2017, p. 28). This supports what the participants expressed, namely, that they find the use of videos an innovative and engaging teaching technique. Furthermore, the authors recommend the use of videos as supplementary tools because they make the learning of English easier for students.

CONCLUSIONS

In view of the data presented above, we can conclude that the videos used in class helped to improve the students’ pronunciation skills, especially their intelligibility component, which received higher scores from both evaluators.

It can also be concluded that pronunciation improvement leads to progress in the speaking skill. As it was mentioned before, pronunciation is a fundamental component of this skill.

Additionally, based on participants´ perceptions, it was also found that they consider the use of videos beneficial, not only for having a better learning experience and practice pronunciation but also for the purposes of gaining knowledge about topics other than merely grammar.

FUTURE RESEARCH

The different scores given by the researcher and the inter-rater could be the subject of another study because the differences may be due to various reasons, such as experience, professional background, etc. This is corroborated by Bøhn and Hansen (2017), who underline that more work is needed to understand raters’ orientations, EFL teacher’s attitudes regarding the assessment of intonation, and other aspects related to different combinations of pronunciation features.

REFERENCES

Alwehaibi, H. O. (2015). The Impact of Using Youtube in EFL Classroom on Enhancing EFL Students’ Content Learning. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 12(2), 121-126.

Argudo, J., Abad, M., Fajardo-Dack, T., & Cabrera, P. (2018). Analyzing a Pre-Service EFL Program through the Lenses of the CLIL Approach at the University of Cuenca-Ecuador. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 11, 65-86. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.4

BavaHarji, M., Alavi, Z., & Letchumanan, K. (2014). Captioned Instructional Video: Effects on Content Comprehension, Vocabulary Acquisition and Language Proficiency. English Language Teaching, 7(5). https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n5p1

Berk, R. A. (2009). Multimedia Teaching with Video Clips: TV, Movies, YouTube, and mtvU in the College Classroom. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning, 5(1)(1–21). https://bit.ly/3s2Rkd3

Bøhn, H., & Hansen, T. (2017). Assessing Pronunciation in an EFL Context: Teachers’ Orientations towards Nativeness and Intelligibility. Language Assessment Quarterly, 14(1), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2016.1256407

Bravo, E., Amante, B., Simo, P., Enache, M., & Fernandez, V. (2011). Video as a new teaching tool to increase student motivation. 2011 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON 2011, 638–642. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON.2011.5773205

British Council (2015). English in Ecuador: An examination of policy, perceptions and influencing factors. https://ei.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/latin-america-research/English%20in%20Ecuador.pdf

Cabrera, P., Espinoza, V., Solano, L., Ulehlova, E. (2017). Exploring the Use of Educational Technology in EFL Teaching: A Case Study of Primary Education in the South Region of Ecuador. Teaching English with Technology, 17(2), 77–86.

Çakir, İ. (2006). The Use of Video as an Audio-Visual Material in Foreign Language Teaching Classroom. In The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET (Vol. 5).

Calle, A. M., Calle, S., Argudo, J., Moscoso, E., Smith, A., & Cabrera, P. (2012). Los profesores de inglés y su práctica docente: Un estudio de caso de los colegios fiscales de la ciudad de Cuenca, Ecuador. http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/5405

Canning-Wilson, C. (2000). Practical Aspects of Using Video in the Foreign Language Classroom (TESL/TEFL). The Internet TESL Journal. http://iteslj.org/Articles/Canning-Video.html

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., & Goodwin, J. M. (1996). Teaching pronunciation: A reference for teachers of English to speakers of other languages. Cambridge University Press.

Celis Nova, J., Onatra Chavarro, C. I., & Zubieta Córdoba, A. T. (2017). Educational Videos: A Didactic Tool for Strengthening English Vocabulary through the Development of Affective Learning in Kids. GIST Education and Learning Research Journal. https://eric.ed.gov/?q=Using+videos+in+teaching+EFL+students&pg=3&id=EJ1146681

Chen, H.-J. H. (2011). Developing and Evaluating SynctoLearn, a Fully Automatic Video and Transcript Synchronization Tool for EFL Learners. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24(2), 117-130.

Council of Europe (2018). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment; Companion Volume with New Descriptors. https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989

Cundell, A. 2008. The integration of effective technologies for language learning and teaching. In Educational technology in the Arabian Gulf: Theory, research and pedagogy, ed. P. Davidson, J. Shewell, and W. J. Moore, 13–23. Dubai: TESOL Arabia.

Davis, C. (1999). Will the Use of Videos Designed for the Purpose of Teaching English Pronunciation Improve the Learners' Production of Discrete Sounds by At Least 80% over a 12 Week Period? Action Research Monograph. Pennsylvania Action Research Network 1998 – 99.

Education First. (2017). 2017 Seventh Edition EF EPI - s. https://www.ef.com.ec/epi/regions/latin-america/ecuador/

Education First. (2019). 2019 Ninth Edition EF EPI-s. www.ef.com/epi

Gilakjani, A. P. (2016). English Pronunciation Instruction: A Literature Review. In International Journal of Research in English Education (Vol. 1). www.ijreeonline.com

Gilakjani, A. P., & Sabouri, N. B. (2016). Why Is English Pronunciation Ignored by EFL Teachers in Their Classes? International Journal of English Linguistics, 6(6), 195. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v6n6p195

Gilakjani, A. P. (2017). English Pronunciation Instruction: Views and Recommendations. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 8(6), 1249-1255. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0806.30

Isiaka, B. (2007). Effectiveness of video as an instructional medium in teaching rural children Agicultural and Environmental Sciences. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 3(3), 105-114. http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu/viewarticle.php?id=363&layout=html

Karim, S., & Haq, N. (2014). An Assessment of IELTS Speaking Test. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 3(3). https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v3i3.6047

Ministerio de Educación. (2019). Currículo de los Niveles de Educación Obligatoria - Subnivel Superior. https://educacion.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2019/09/EGB-Superior.pdf

Moedjito. (2016). The Teaching of English Pronunciation: Perceptions of Indonesian School Teachers and University Students. English Language Teaching, 9(6), 30-41.

Morley, J. (1991). The Pronunciation Component in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. TESOL Quaterly, 25(1), 51-74.

Muslem, A., Mustafa, F., Rahman, A., Usman, B. (2017). The Application of Video Clips with Small Group and Individual Activities to Improve Young Learners’ Speaking Performance. Teaching English with Technology, 17(4), 25–37.

Nuñez, P.A., (2015). Teacher´s Book - Level 2. Quito, Ecuador: Norma.

Ortega Auquilla, D. P., & Fernández, R. A. (2017). La Educación Ecuatoriana en Inglés: Nivel de Dominio y Competencias Lingüísticas de los Estudiantes Rurales. Revista Scientific, 2(6), 52-73. https://doi.org/10.29394/scientific.issn.2542-2987.2017.2.6.3.52-73

Park, Y., & Jung, E. (2016). Exploring the Use of Video-Clips for Motivation Building in a Secondary School EFL Setting. English Language Teaching, 9(10), 81-89.

Ramanarayanan, V., Lange, P. L., Evanini, K., Molloy, H. R., & Suendermann-Oeft, D. (2017). Human and Automated Scoring of Fluency, Pronunciation and Intonation During Human–Machine Spoken Dialog Interactions, 1711-1715. https://doi.org/10.21437/interspeech.2017-1213

Ratnawati, R., & Faridah, D. (2017). Engaging Multimedia into Speaking Class Practices: Toward students’ Achievement and Motivation. Script Journal: Journal of Linguistic and English Teaching, 2(2), 167-176. https://doi.org/10.24903/sj.v2i2.135

Richards, J. C., & Renadya, W. A. (2002). Methodology in Language Teaching 2002scanned.pdf. Cambridge University Press.

Setter, J., & Jenkins, J. (2004). State-of-the-Art Review Article. Article in Language Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480500251X

Tejeda, A. C. T., & Santos, N. M. B. (2014). Pronunciation Instruction and Students’ Practice to Develop Their Confidence in EFL Oral Skills. Profile: Issues in Teachers´ Professional Development, 16(2), 151-170. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.46146

Yassaei, S. (n.d). Using Original Video and Sound Effects to Teach English, English Teaching Forum, 2012. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ971236

Yasin, B., Mustafa, F., & Permatasari, R. (2018). How Much Videos Win Over Audios in Listening Instruction for EFL Learners. In TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology (Vol. 17).

Yates, L., & Zielinski, B. (2009). Give it a go: Teaching pronunciation to adults. http://www.ag.gov.au/cca

Yükselir, C., & Kömür, Ş. (2017). Using Online Videos to Improve Speaking Abilities of EFL Learners. European Journal of Education Studies i. 3. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.495750